Containerized Django Development: Part 2

Experimenting CORS with Django Views

1.0 Overview

In our last adventure, we embarked on a journey to containerize our Django application with Docker and GraphQL. We even touched upon the guardians of our API: CORS and CSRF. But that was just a glimpse into their power! If you have not read the previous article, I will highly recommend it reading here.

This time, we’re diving deep into the trenches of CORS implementation. We’ll explore the real-world challenges I faced when deploying my application to production – those “oh no!” moments when things didn’t go quite as planned (because, let’s be honest, who hasn’t been there?).

And fear not, fellow developers! We won’t leave you stranded in a sea of confusion. I’ll guide you through the proper implementation of CORS and CSRF in Django, demystifying those tricky configurations that often send newbies running for the (sometimes dangerous) comfort of @csrf_exempt.

You can find the complete source code with a step-by-step setup guide here. But in this article, we’re all about the “why” and the “how,” so get ready for a deep dive into the theory behind these security essentials!

2.0 Taking Down the Walls (Temporarily!)

Before we construct our fortress of security, let’s first understand why these safeguards are so important. To do that, we’ll temporarily disable our defenses and see what happens when chaos reigns free! Our Django application relies on two key files for CORS and CSRF protection: settings.py and the .env file. Think of the .env file as our security control panel, where we define who’s allowed to knock on our API’s door. It contains two crucial variables:

1. DJANGO_ADMIN_SERVICE_ALLOWED_HOSTS: This is our guest list, specifying which domains have access to our API endpoints. Initially, it’s set to an asterisk (*), meaning everyone is invited to the party! (Not ideal for security, but great for our experiment).

2. DJANGO_ADMIN_CSRF_TRUSTED_ORIGIN: This variable determines who we trust with our secret CSRF tokens. It’s initially empty, meaning we’re not handing out any secret handshakes just yet.

The settings.py file, on the other hand, is where the actual CORS and CSRF magic happens. It contains the code that enforces these security measures based on the rules we define in our .env file.

ALLOWED_HOSTS = os.getenv('ALLOWED_HOSTS', '').split(',')

CORS_ALLOW_CREDENTIALS = True

The code snippet provided above contains the configuration related to CORS and CSRF protection. Now, let’s say we want to tighten security and only allow requests from localhost. We can update our .env file like this:

DJANGO_ADMIN_SERVICE_ALLOWED_HOSTS=”localhost”

DJANGO_ADMIN_CSRF_TRUSTED_ORIGIN=”http://localhost:4200″

This tells our Django app: “Hey, only allow requests from applications running on localhost. And while you’re at it, only trust http://localhost:4200 with CSRF tokens.”

Of course, we can add multiple comma-separated domains and origins if we have a more extensive guest list. But for our experiment, we’ll keep it simple.

Now, for the fun part! To truly appreciate the importance of CORS and CSRF, we’ll temporarily comment out all the related configurations in settings.py. This essentially reverts to Django’s default settings, leaving our API wide open.

Let the testing begin!

3.0 A Classic Django Tale: The Case of the Vanishing Token

Before we delve into the complexities of GraphQL, let’s revisit the familiar territory of Django’s view-based forms. After all, every Django developer starts their journey here! We will remove all the custom CORS and CSRF configuration from our settings file. The code will look as follows:

from pathlib import Path

import os

# Build paths inside the project like this: BASE_DIR / 'subdir'.

BASE_DIR = Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent

# SECURITY WARNING: keep the secret key used in production secret!

SECRET_KEY = os.getenv('SECRET_KEY', '')

# SECURITY WARNING: don't run with debug turned on in production!

DEBUG = os.getenv('DEBUG', 'True') == 'True'

# Application definition

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.messages',

"daphne", # must be placed before django.contrib.staticfiles

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

'django_playground',

]

MIDDLEWARE = [

'django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware',

'django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware',

'django.middleware.common.CommonMiddleware',

'django.middleware.csrf.CsrfViewMiddleware',

'django.contrib.auth.middleware.AuthenticationMiddleware',

'django.contrib.messages.middleware.MessageMiddleware',

'django.middleware.clickjacking.XFrameOptionsMiddleware',

]

ROOT_URLCONF = 'django_playground.urls'

...

3.1 The Setup

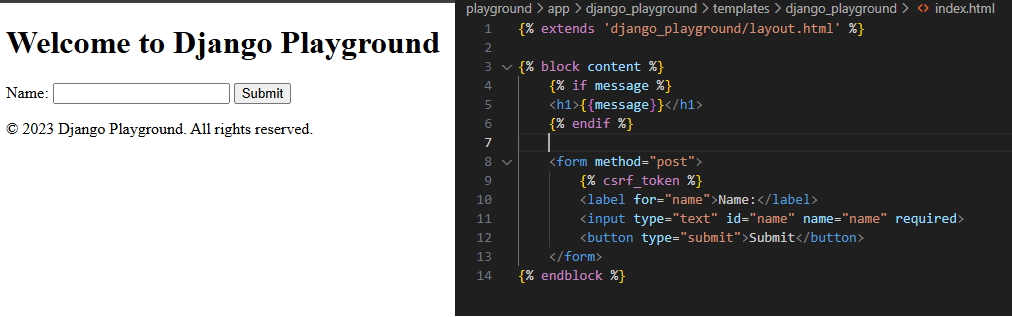

Imagine a classic Django scene: a simple form where you enter your name and, upon submission, are greeted with a friendly “Hello, [your name]!” But lurking beneath this seemingly innocent interaction lies a critical security challenge.

Here’s the twist:

1. No Trust, No Entry: We’ve stripped our settings.py file bare, removing all custom CORS and CSRF configurations. Our Django application is now a fortress, trusting no one except itself.

2. The Form Beckons: We open our browser, and there it is – a basic form, eagerly awaiting our input. We type in our name, hit submit, and voilà! The page displays the personalized greeting.

But here’s the secret ingredient: our index.html file contains a hidden gem – the {% csrf_token %} variable, nestled within the form. This seemingly innocuous piece of code is our first line of defense against CSRF attacks.

3.2 The Experiment

Now, let’s don our detective hats and conduct a little experiment. We’ll open an incognito window (because every good detective needs to go undercover) and submit the form. Then, using our trusty Chrome DevTools (our magnifying glass, if you will), we’ll inspect the HTTP request and response headers to uncover the secrets of Django’s CSRF protection.

But the plot thickens! We’ll then remove the {%csrf_token%} from our index.html form and repeat the experiment. Will our form submission still succeed? Or will Django’s security measures thwart our attempt?

This little exercise will reveal the crucial role that {%csrf_token%} plays in safeguarding our application from CSRF attacks. Get ready to witness the magic (and importance) of Django’s built-in security mechanisms!

3.3 Django View: Unmasking the CSRF Token

To understand how Django’s CSRF protection works, we’ll conduct a series of tests using an incognito window, ensuring a clean browser state with no pre-existing cookies or sessions.

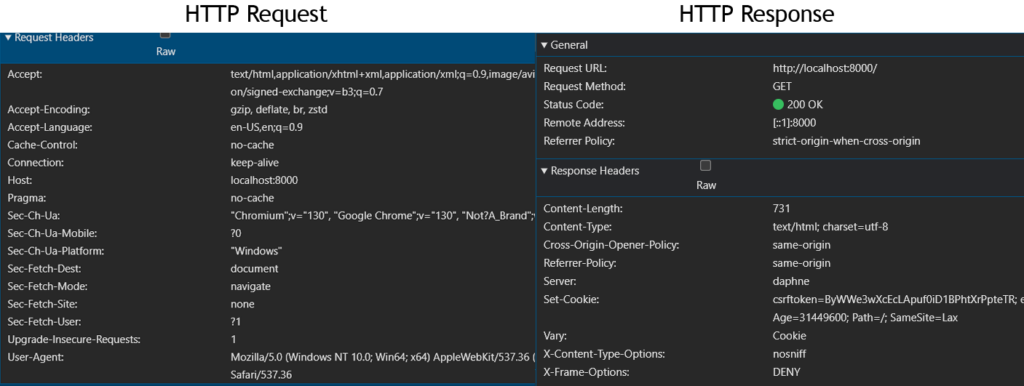

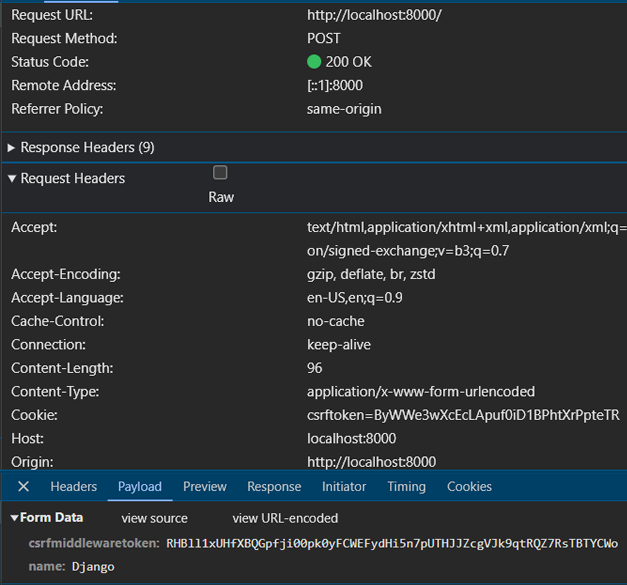

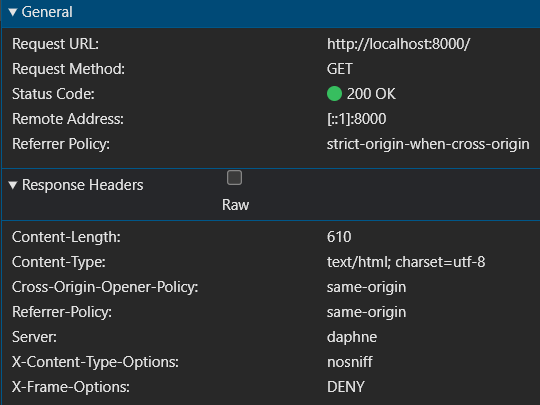

Our first step is to simply load the homepage. As we peer into the network tab of our developer tools, we notice something interesting. The initial request, devoid of any identifying cookies or authorization headers, sails through unimpeded. Django, it seems, is welcoming to first-time visitors. However, a closer look at the response reveals a Set-Cookie header, subtly instructing the browser to store a csrftoken. This is our first encounter with Django’s security measures, quietly setting the stage for future interactions. We can notice a couple of things in the HTTP response returned by our Django application.

1. No authorization headers: The request does not contain any cookie or authorization headers.

2. Set-Cookie Header: On the other hand, when you observe the HTTP response, you can see the header called ‘Set-Cookie’. This is our Django application instructing the browser to set the cookies returned as the value.

3. Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy (COOP) header: When we open a webpage in our browser, it loads within a specific browsing context—a container, like a browser window, where the page operates. If we embed an iframe on that page, the iframe has its own browsing context since it can load content from external sites. Without a restrictive header, all web pages and embedded elements like iframes could potentially share a global browsing context. This shared access could allow an attacker to gain unauthorized entry to another page’s browsing context within the same window and potentially access sensitive information. COOP enables the browser to control and isolate each page’s browsing context. For instance, setting the header to ‘same-origin’ ensures that only pages from the same origin (e.g., localhost) can access the browsing context of this page. For more in-depth details, I’ve included additional links in the references section. This header is closely related to CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) since it allows us to define how external applications with different origins can interact with our webpage.

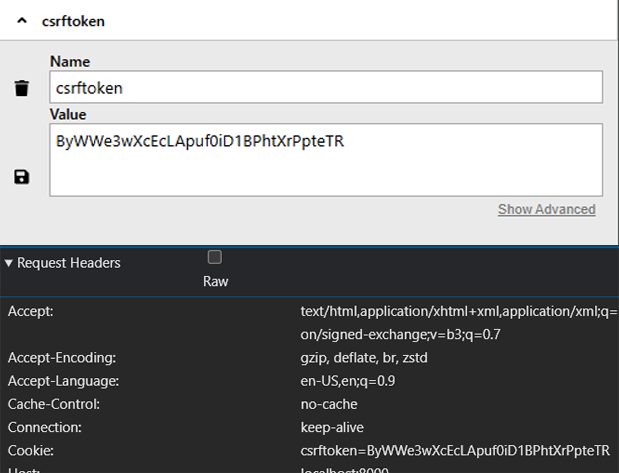

We can observe that our browser has stored the ‘csrftoken’ in cookies, as directed by our backend application. Interestingly, we also notice that our initial HTTP GET request succeeded even though the browser didn’t send a CSRF token to the backend.

Intrigued, we reload the page, simulating a returning visitor. This time, the request proudly displays the csrftoken within its Cookie header, like a badge of authenticity. Django, recognizing the token, grants access without hesitation.

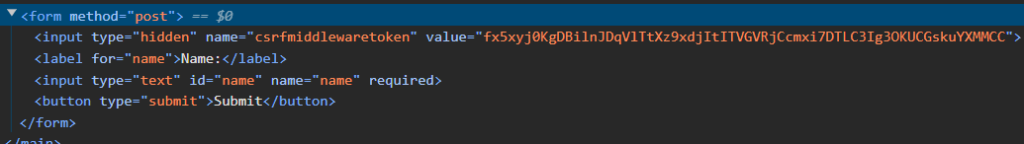

But the plot thickens! As we delve deeper, we observe a curious discrepancy. The csrftoken nestled within the browser’s cookie jar differs from the {% csrf_token %} embedded in our index.html form. This unexpected twist raises questions about the purpose of this seemingly duplicate token and its role in the grand scheme of CSRF protection.

While the cookie-based token acts as a long-term pass, granting access for the duration of our session, its form-bound counterpart plays a more dynamic role. This token, regenerated with every page load, ensures that each form submission carries a unique and unpredictable identifier.

Think of it as a one-time password, valid only for that specific form interaction. This prevents malicious actors from replaying old requests or forging submissions, as the token embedded within the form’s payload must perfectly match the one expected by the server.

This intricate dance between the two tokens—the persistent cookie and the ephemeral form twin—ensures a robust defense against CSRF attacks. The cookie-based token verifies the user’s identity and establishes a trusted session, while the form-bound token acts as a short-lived key, unlocking the door only for that specific request.

On submitting the form, we can see that our CSRF token stored in the cookie is sent as the request header. The csrf token that was included in our index.html form is sent as the payload of the POST request. The same thing will happen if we send a POST request from our Django application using JavaScript and we do not include the csrf token in our payload.

Django by default uses form data when submitting a POST request. It adds the token in a hidden input field with a predefined name so that it is submitted during the POST request. If we remove the line of code ‘{% csrf_token %}’ in our index.html we will see that no input field is present for csrf token when we load our web page. If we now try to submit a POST request, we will receive an error in our page that says:

Forbidden (403)

CSRF verification failed. Request aborted.

This means that our backend threw a 403 error because it did not receive a CSRF token. However, we did send one of the CSRF tokens using the ‘Set-Cookie’ header. But our CSRFMiddleware blocked the request as it did not receive a valid token in the POST requests payload.

With the csrf_token still banished from our index.html, we embark on a fresh start, opening a pristine incognito window devoid of any lingering cookies. As we load the index page, a curious phenomenon unfolds: the Set-Cookie header, previously a constant companion, has vanished from the response.

This unexpected turn of events suggests a hidden condition for Django’s cookie distribution. It appears that Django only bestows its csrftoken upon pages that already possess a valid token within their form. It’s like a secret club, where only those with the password gain access to the secret handshake.

This revelation has significant implications for API interactions. When external applications, such as our Angular frontend, communicate with our Django backend, they typically receive JSON responses. These responses, unlike HTML pages, lack the necessary form structure to embed a CSRF token.

Therefore, with Django’s default settings, we shouldn’t expect a Set-Cookie header when calling our GraphQL endpoint from an external application. Django, it seems, reserves its cookie distribution for those playing by the rules of traditional form-based interactions.

This intriguing discovery leads us to the next chapter of our investigation: testing the GraphQL endpoint from an external application. Armed with our newfound knowledge, we prepare to explore the challenges and solutions for securing API interactions in a world dominated by JavaScript frontends and token-based authentication.

4.0 Conclusion

While our initial goal was to cover the complete implementation of CORS and CSRF for our GraphQL API in this article, it seems we’ve reached the limits of our current platform (WordPress Elementor is the culprit here). Fear not, for this is merely a pause in our journey, not the end!

In this part, we’ve laid the groundwork for understanding CORS and CSRF, exploring their core concepts through practical examples and experiments. We’ve ventured into the world of cross-origin requests, encountering the challenges and solutions associated with securing our Django application from unauthorized access.

We’ve witnessed the browser’s role as a CORS enforcer, the importance of configuring ALLOWED_HOSTS, and the intricacies of preflight requests. Through these explorations, we’ve gained valuable insights into diagnosing and resolving CORS-related issues.

But our adventure doesn’t end here! In the next installment of this series, we’ll delve deeper into the realm of GraphQL, exploring the implementation of CSRF protection for API endpoints. We’ll uncover the techniques for securing POST requests from external applications while maintaining a robust security posture.

Stay tuned for the final chapter, where we’ll bring together all the pieces of the puzzle and achieve a comprehensive solution for securing our Django GraphQL API. Until then, happy coding and may your applications remain safe from the clutches of cross-origin attacks!

References

2. https://github.com/zuhairmhtb/DjangoPlayground

3. https://github.com/zuhairmhtb/ThePortfolioAdmin

4. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy

5. https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/HTTP_Headers_Cheat_Sheet.html

6. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/Sec-Fetch-Mode

7. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/Host